Your Face Is Public Property - The Cyberpsychology of Facial Recognition in a Post-Privacy World

SURVEILLANCE & SOCIETY

When Machines Never Forget a Face

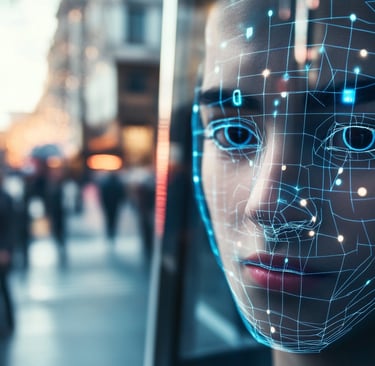

Every morning, millions of people unlock their phones with a glance. The technology feels magical—your face becomes a key, instant and effortless. But this same convenience has unleashed something far more complex into our world: the age of perpetual recognition. From airport security to grocery stores, concert venues to city sidewalks, facial recognition systems are quietly cataloging our movements, expressions, and identities. What began as a tool for personal convenience has evolved into an invisible network that watches, remembers, and analyzes our faces wherever we go.

This shift raises a profound psychological question: What happens to the human psyche when anonymity—a fundamental aspect of public life for millennia—suddenly disappears? As facial recognition psychology becomes increasingly relevant to our daily experience, we must grapple with the mental and emotional consequences of living under constant biometric surveillance. The implications extend far beyond privacy concerns, touching the very core of how we see ourselves and navigate the world around us.

The Digital Mirror - From Face ID to Full-Time Tracking

The journey from convenient personal authentication to pervasive public surveillance represents one of the most significant shifts in how technology intersects with human psychology. When Apple introduced Face ID in 2017, it normalized the idea that our faces could serve as passwords. The technology felt personal, secure, and under our control—a digital reflection that recognized us and us alone.

But facial recognition technology has evolved far beyond personal devices. Today's systems can identify individuals across vast networks of cameras, creating what researchers call the "digital gaze"—an omnipresent electronic eye that never blinks, never forgets, and never stops watching. Unlike the brief moment of recognition when unlocking a phone, this surveillance operates continuously, tracking our movements through shopping centers, monitoring our expressions at traffic lights, and cataloging our presence at public events.

The psychological difference between consensual and non-consensual facial recognition cannot be overstated. When we choose to unlock our phones with our faces, we maintain agency over the interaction. We decide when to engage with the technology and can easily opt out by using a passcode instead. However, public facial recognition systems strip away this choice, creating what surveillance and public identity researchers describe as a state of "forced visibility."

This digital gaze operates through increasingly sophisticated algorithms that can identify individuals even when they're partially obscured, wearing sunglasses, or captured from unusual angles. The technology has become so advanced that it can recognize people across decades of aging, analyze micro-expressions for emotional states, and even attempt to predict behavior based on facial features—a practice that raises serious concerns about algorithmic bias and digital profiling.

The Psychology of Being Always Recognizable

Living under constant facial surveillance fundamentally alters human behavior in ways both subtle and profound. When we know we might be recognized at any moment, our relationship with public spaces undergoes a dramatic transformation. The psychological impact of facial tracking extends far beyond mere privacy concerns, affecting our self-consciousness, spontaneity, and sense of freedom.

The phenomenon of heightened self-awareness represents one of the most immediate psychological effects. Social psychologists have long understood that being watched changes behavior—a principle known as the "observer effect" or "Hawthorne effect." However, facial recognition technology amplifies this effect exponentially. Unlike human observers who might look away or forget what they've seen, digital systems create permanent records, leading to what researchers term "panopticon anxiety"—the stress of never knowing when you're being watched while simultaneously assuming you always are.

This constant potential for recognition creates a state of perpetual performance anxiety. People report feeling more conscious of their facial expressions in public, suppressing emotions they might normally display, and avoiding certain locations or activities they fear might be recorded and analyzed. The psychological burden of maintaining a "public face" at all times can be exhausting, leading to what some researchers call "facial facade fatigue."

The loss of anonymity also impacts social behavior in unexpected ways. Anonymity has traditionally served as a psychological safety valve, allowing people to explore different aspects of their personalities, engage in spontaneous interactions, and take social risks without fear of permanent consequences. When facial recognition systems eliminate this anonymity, they may inadvertently stifle human spontaneity and social experimentation.

Biometric surveillance effects extend to our sense of personal autonomy and privacy. The knowledge that our faces are being continuously analyzed can create a feeling of psychological violation, even when no obviously harmful consequences result. This effect is particularly pronounced among individuals who have experienced trauma, marginalized communities who have historically faced discrimination, and those who simply value privacy as a fundamental human right.

Consent, Coercion, and Normalization

The issue of informed consent in facial recognition surveillance reveals a fundamental tension between technological capability and psychological autonomy. Unlike other forms of data collection where users can theoretically read terms of service and make informed decisions, public facial recognition often operates without explicit consent or even awareness.

This absence of meaningful consent contributes to what psychologists call "privacy fatigue"—a state of learned helplessness where individuals become overwhelmed by the complexity and ubiquity of surveillance technologies. When people feel they have no realistic way to opt out of facial recognition systems, they often experience a psychological shift from resistance to resignation. This progression mirrors the stages of grief, moving from denial and anger to eventual acceptance of a new reality.

The normalization of surveillance represents perhaps the most concerning psychological adaptation. As facial recognition technology becomes more common, society undergoes a gradual recalibration of privacy expectations. What once seemed invasive becomes routine; what once felt unacceptable becomes normal. This process of surveillance normalization doesn't happen overnight but occurs through a series of small compromises and technological creep.

Children and young adults who have grown up with facial recognition technology may experience this normalization most acutely. Having never known a world without digital surveillance, they may lack the psychological framework to understand what has been lost. This generational shift in privacy expectations could have profound implications for future democratic participation, protest movements, and individual autonomy.

The psychological concept of "privacy fatigue" also manifests in behavioral changes. When people feel overwhelmed by the complexity of surveillance technologies, they often respond by either becoming hypersensitive to privacy issues or, more commonly, by disengaging entirely from privacy concerns. This disengagement can look like acceptance but often masks underlying anxiety and helplessness.

The Faceprint Economy

Behind the technology lies a complex economy built on the commodification of human faces. Companies have discovered that biometric data, particularly facial recognition data, represents an extraordinarily valuable resource. Unlike passwords or credit card numbers, faces cannot be easily changed, making them ideal for creating permanent digital profiles that can be bought, sold, and shared across platforms.

The Clearview AI controversy exemplifies the psychological and ethical implications of this faceprint economy. Clearview AI, founded in 2017, created a facial recognition database by scraping billions of photos from social media platforms, websites, and other online sources without users' knowledge or consent. The company then sold access to this database primarily to law enforcement agencies, creating a system where virtually anyone's face could be identified from a single photograph.

The psychological impact of learning about Clearview AI's database was profound for many people. Suddenly, photos they had shared on social media years earlier—pictures they may have forgotten about or deleted—had become part of a permanent surveillance infrastructure. The retroactive nature of this data collection created a unique form of psychological violation, as people realized their past selves had been unknowingly enrolled in a surveillance system they never consented to join.

The Clearview AI case also highlighted the power dynamics inherent in facial recognition technology. While the company's database was primarily marketed to law enforcement, the technology could theoretically be used by anyone with access to identify individuals in public spaces. This asymmetry of power—where institutions can identify individuals but individuals cannot identify institutions—creates what surveillance researchers call "surveillance inequality."

The commodification of facial data raises profound questions about ownership and consent. If companies can create permanent databases of human faces without permission, what does this mean for personal autonomy? The psychological impact extends beyond individual privacy to encompass broader concerns about democratic participation, freedom of association, and the right to be forgotten in an age of permanent digital memory.

Rebellion and the Fight for the Face

As awareness of facial recognition surveillance has grown, so too has resistance to it. This pushback takes many forms, from high-tech solutions to simple acts of creative defiance, all reflecting a deep human need to maintain some degree of anonymity and control over personal identity.

Anti-surveillance fashion has emerged as one of the most visible forms of resistance. Designers have created clothing and accessories specifically designed to confuse facial recognition systems—garments with infrared LEDs that overwhelm camera sensors, makeup patterns that disrupt algorithmic analysis, and masks that maintain human expressiveness while blocking digital identification. These innovations represent more than mere fashion statements; they embody a psychological assertion of autonomy in the face of technological determinism.

The development of AI decoys and deepfake technology has created additional tools for evading surveillance, though these solutions come with their own ethical complexities. Some privacy advocates have created services that generate synthetic faces or digitally alter appearances in real-time, allowing individuals to maintain visual presence while avoiding recognition. However, these technologies also raise concerns about authentication, trust, and the potential for misuse.

Perhaps more significantly, there's a growing psychological movement focused on reclaiming public anonymity. Support groups have formed for people experiencing surveillance anxiety, mental health professionals are developing new therapeutic approaches for privacy-related trauma, and civil rights organizations are working to establish "facial recognition-free zones" in cities around the world.

The psychological drive to maintain anonymity appears to be deeply rooted in human nature. Research suggests that the ability to be anonymous in public spaces serves important psychological functions, including stress relief, identity exploration, and creative expression. The fight to preserve these spaces represents more than a political struggle—it's a battle for fundamental aspects of human psychological well-being.

Some communities have taken collective action to resist facial recognition deployment, recognizing that individual solutions may be insufficient against institutional surveillance. Cities like San Francisco, Boston, and Portland have banned or restricted government use of facial recognition technology, while advocacy groups continue to push for broader legislative protections.

Conclusion

The rise of facial recognition technology has fundamentally altered the psychological landscape of public life. We are witnessing the emergence of a post-privacy world where anonymity—once a basic feature of human social interaction—has become a luxury that fewer and fewer people can afford. The psychological consequences of this shift extend far beyond privacy concerns, affecting our self-expression, social behavior, and basic sense of autonomy.

The research on facial recognition psychology reveals that biometric surveillance effects are both immediate and long-lasting. People living under constant surveillance report higher levels of anxiety, increased self-consciousness, and a general sense that their freedom of expression has been curtailed. These effects are particularly pronounced in communities that have historically faced discrimination or persecution, where facial recognition technology can amplify existing power imbalances and social inequalities.

As we navigate this new reality, we must grapple with fundamental questions about the kind of society we want to create. The technology itself is not inherently good or evil—its impact depends on how we choose to deploy it, regulate it, and integrate it into our social structures. The psychological evidence suggests that unrestricted facial recognition surveillance poses significant risks to human well-being and democratic values.

The future of facial recognition technology will likely be shaped by ongoing tensions between convenience and privacy, security and freedom, technological capability and human values. As individuals and as a society, we have the opportunity to influence this trajectory through our choices, our advocacy, and our willingness to engage with these complex issues.

The question we must ask ourselves is not whether facial recognition technology will continue to advance—it almost certainly will. Instead, we must consider what safeguards, regulations, and social norms we need to preserve human dignity and psychological well-being in an age of ubiquitous surveillance.

If our faces are no longer private, what does that mean for our sense of self and freedom? The answer to this question will determine not just the future of privacy, but the future of human autonomy itself. The conversation about facial recognition psychology is just beginning, and all of us have a stake in how it unfolds.

How do you feel about being recognized by machines in public? Have you noticed changes in your behavior in spaces where you know facial recognition might be in use? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below—your perspective could help others understand the real-world psychological impacts of living in a post-privacy world.