The Evolution of Cyberpsychology - From the Early Internet to the Age of AI

MIND & MACHINE

Introduction

What happens to human psychology when our lives increasingly unfold in digital spaces that didn't exist just decades ago? Since the early 1990s, when the internet began its transformation from an academic curiosity to a global phenomenon, our minds have been adapting to fundamentally new ways of connecting, learning, working, and even existing. We've witnessed perhaps the most rapid transformation of human behavior in history—not through biological evolution, but through our intricate dance with technology. This relationship between humans and digital environments has given birth to an entirely new field: cyberpsychology.

Cyberpsychology examines how technology influences our cognitive processes, emotional responses, social interactions, and identity formation. As we stand at the frontier of artificial intelligence and immersive virtual worlds, understanding this psychological interplay has never been more crucial. What began as a niche discipline studying basic online interactions has evolved into a critical lens for understanding human behavior in the 21st century.

A Brief History of Cyberpsychology

Origins and Early Developments

The term "cyberpsychology" emerged in the early 1990s, coinciding with the mainstream adoption of the World Wide Web. Dr. John Suler, a pioneer in the field, began studying online behavior in 1996, observing how people interacted in primitive chat rooms and forums. His groundbreaking work on the "Online Disinhibition Effect" identified how the internet's anonymity, invisibility, and asynchronicity fundamentally altered human behavior, often making people more willing to self-disclose or act out in ways they wouldn't in face-to-face interactions.

During this nascent period, researchers primarily focused on understanding basic psychological processes like identity presentation, social connection, and the formation of virtual communities. The field was inherently interdisciplinary from the start, drawing from cognitive psychology, social psychology, human-computer interaction, communication studies, and sociology.

Institutional Recognition

By the early 2000s, cyberpsychology began gaining formal academic recognition. In 2001, the American Psychological Association established Division 46: Media Psychology and Technology, acknowledging the growing importance of digital environments in human experience. The first specialized academic journals emerged, including CyberPsychology & Behavior (now CyberPsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking) in 1998, providing dedicated venues for research in this emerging field.

The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland launched the world's first Master's degree in Cyberpsychology in 2006, marking a significant milestone in the field's institutional recognition. As smartphones and social media platforms proliferated throughout the 2000s and 2010s, university programs dedicated to cyberpsychology expanded globally, reflecting the growing need for specialists who could bridge psychological understanding with technological expertise.

The Evolution of Online Behavior

The Early Web Era (1990s)

The early internet environment was text-dominated, with users connecting through dial-up modems to access basic websites, email, and rudimentary chat rooms. During this period, cyberpsychology research focused on fundamental questions: How do people form identities online? What motivates participation in virtual communities? What new social dynamics emerge in text-based communication?

Early studies found fascinating differences between online and offline behavior. People experimented with multiple identities, sometimes presenting entirely different personas online. The absence of nonverbal cues led to miscommunication but also created opportunities for connection unhindered by physical appearance or social status. This era saw what MIT professor and pioneering researcher Sherry Turkle described as a separate space where people could explore alternative versions of themselves, experimenting with identity in ways previously impossible.

Web 2.0 and Social Media (2000s-2010s)

The advent of Web 2.0 technologies and social media platforms fundamentally transformed online behavior. As platforms like Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005), and Twitter (2006) gained popularity, online identity became increasingly tied to real-world identity. The anonymity that characterized early internet spaces gave way to persistent digital identities linked to our offline selves.

Cyberpsychology research during this period expanded dramatically to investigate phenomena like:

Digital self-presentation: How users carefully curate online personas through profile management and selective content sharing

Social comparison: The psychological impacts of constant exposure to others' (often idealized) lives

Attention economy: How platforms compete for and monetize user attention, and the psychological techniques employed to maximize engagement

Online disinhibition: Both toxic behaviors like cyberbullying and trolling, and positive outcomes like increased willingness to seek help or join support communities

The smartphone revolution beginning with the iPhone in 2007 made these digital environments continuously accessible, blurring the boundaries between online and offline life. By the mid-2010s, researchers were documenting profound shifts in behavior, with studies showing the average American checking their phone 96 times daily—approximately once every 10 minutes of waking life.

The Immersive and AI-Driven Internet (2020s)

Today, we're witnessing another transformation. Virtual reality, augmented reality, and AI-powered environments are creating more immersive and responsive digital spaces. The line between human and machine interaction is blurring with AI systems like GPT-4 that can engage in nuanced conversations, generate creative content, and even mimic emotional intelligence.

Current cyberpsychology research explores unprecedented questions:

How does embodied cognition function in virtual reality environments where physical laws can be manipulated?

What are the psychological impacts of relating emotionally to artificial entities with increasingly human-like capabilities?

How do machine learning algorithms that predict and shape our preferences affect autonomy and decision-making?

What new forms of identity and community emerge in metaverse-like environments where users have agency over reality itself?

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated our collective migration to digital spaces, with remote work, virtual socializing, and online learning becoming normalized almost overnight. This mass digital adoption has provided cyberpsychologists with natural experiments at unprecedented scale, revealing both the remarkable adaptability of human psychology and its vulnerability in digital contexts.

Key Researchers and Landmark Studies

Pioneering Figures

Dr. John Suler (Rider University) published "The Psychology of Cyberspace" in 1996, one of the first comprehensive examinations of online behavior. His work on the Online Disinhibition Effect remains fundamental to understanding internet behavior, identifying six factors that lead people to behave differently online: anonymity, invisibility, asynchronicity, solipsistic introjection, dissociative imagination, and minimization of authority.

Dr. Sherry Turkle (MIT) has documented our evolving relationship with technology for over three decades. Her trilogy of books—"The Second Self" (1984), "Life on the Screen" (1995), and "Alone Together" (2011)—charts our progression from seeing computers as mere tools to viewing them as potential companions and extensions of our identity. Her research consistently examines how technology reshapes our understanding of ourselves, our relationships with others, and our conception of what it means to be human in an increasingly digital world.

Dr. BJ Fogg (Stanford University) founded the Persuasive Technology Lab in 1998, pioneering research into how digital technologies can influence human behavior. His behavioral model explaining how behavior change requires a combination of motivation, ability, and appropriate triggers has significantly influenced both academic understanding and commercial application, particularly in how companies design habit-forming applications and services.

Landmark Studies

The Stanford Internet and Society Studies (2000-present), directed by Dr. Norman Nie, provided some of the first large-scale empirical evidence on how internet use affects social relationships and psychological well-being. These studies challenged both utopian and dystopian narratives, revealing complex patterns where technology's effects depended on how it was used rather than the technology itself.

The Facebook Emotional Contagion Study (2014), conducted by Facebook's research team in collaboration with Cornell University, experimentally manipulated the emotional content appearing in 689,003 users' news feeds to test whether emotional states could be transferred via social networks. The study demonstrated that emotional contagion occurs online even without direct interaction, but also sparked massive ethical debates about informed consent in digital research.

The iGen Studies by Dr. Jean Twenge (2017-present) have documented significant correlations between smartphone and social media use and declining mental health among post-Millennials (born 1995-2012). Her research has identified concerning trends, including sharp increases in depression, anxiety, and suicide rates coinciding with widespread smartphone adoption, prompting renewed focus on digital wellness.

The Human Screenome Project (2020), led by researchers at Stanford and Pennsylvania State University, moves beyond self-reported screen time to capture and analyze actual digital behavior through screenshots taken every five seconds. This methodology has revealed the extraordinarily fragmented nature of our digital lives, with the average user switching tasks every 19 seconds when on their devices.

Current Research Frontiers

Today's cyberpsychology research is increasingly focusing on:

Algorithmic influence - Researchers like Dr. Zeynep Tufekci (University of North Carolina) are investigating how recommendation systems and personalization algorithms shape behavior, beliefs, and social dynamics.

Digital well-being - Dr. Amy Orben (University of Cambridge) leads research challenging simplistic narratives about technology's effects, using advanced statistical methods to understand the nuanced relationships between digital technology use and psychological outcomes.

Online extremism and radicalization - Dr. Megan Squire (Elon University) combines data science with psychological insights to understand how online communities can accelerate extremist beliefs.

Human-AI interaction - Dr. Kate Darling (MIT) examines the psychological dimensions of our relationships with robots and AI systems, particularly how humans readily anthropomorphize and form emotional attachments to machines.

"Digital phenotyping" - Pioneered by Dr. Thomas Insel (former Director of the National Institute of Mental Health), this approach uses passive data collection from smartphones to identify behavioral patterns that may indicate mental health conditions, potentially revolutionizing psychological assessment.

The Theoretical Framework of Cyberpsychology

As the field has matured, researchers have developed theoretical frameworks that help explain human behavior in digital environments:

The Proteus Effect

Named after the shape-shifting Greek god, this theory proposed by Dr. Nick Yee and Dr. Jeremy Bailenson of Stanford University demonstrates how the digital representation of oneself (an avatar) influences behavior. Their experiments have shown that using taller avatars leads individuals to negotiate more aggressively, while more attractive avatars increase confidence and interpersonal distance management. This effect reveals how digital self-representation doesn't just express identity but actively shapes behavior.

The Hyperpersonal Model

Developed by Dr. Joseph Walther, this theory explains why computer-mediated communication sometimes produces stronger relationships than face-to-face interaction. By allowing selective self-presentation, idealization of partners, and communication management, digital channels can create "hyperpersonal" interactions that exceed typical relationship development. This model helps explain the intensity of online relationships and how meaningful connection can occur even in text-based environments.

The Extended Self Theory

Originally proposed by consumer researcher Russell Belk and later updated for the digital age, this theory examines how people incorporate digital possessions and identities into their sense of self. From social media profiles to virtual goods in games, digital objects now form critical components of identity, with their loss potentially triggering genuine grief responses similar to physical possessions.

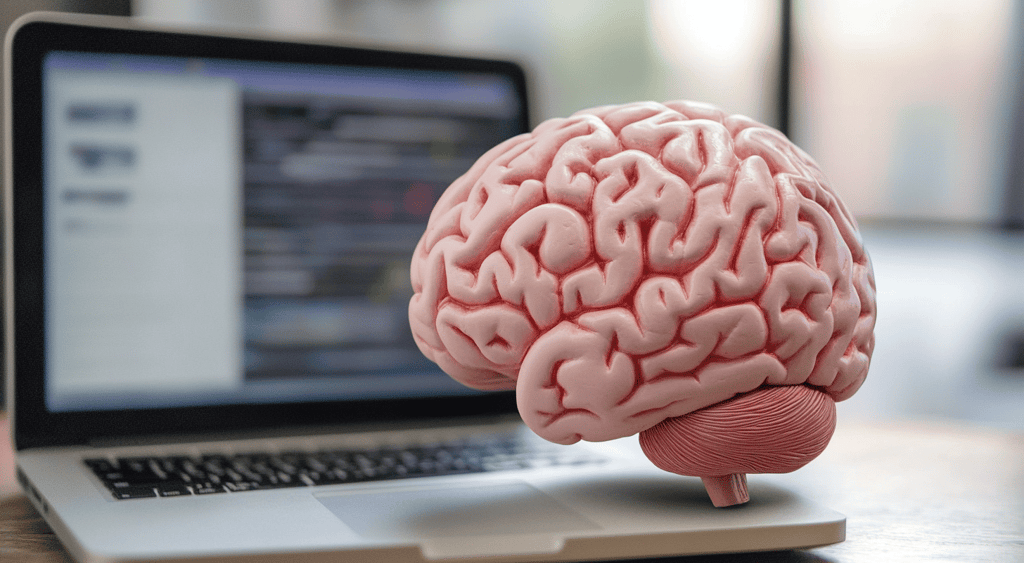

The Smartphone Brain

Dr. Larry Rosen's research investigates how smartphones essentially function as an external brain, altering cognitive processes including attention, memory, and executive functioning. His studies have documented how people sometimes perceive phantom vibrations from their phones when none occurred and demonstrated that merely having a smartphone visible nearby can reduce a person's cognitive capacity, showing technology's profound impact on fundamental mental processes.

Ethical Considerations and Future Directions

As cyberpsychology continues evolving, several critical ethical considerations have emerged:

Digital divides - How do we address disparities in access to technology that may create psychological advantages for some populations while excluding others?

Digital consent - What constitutes meaningful informed consent in environments where terms of service go unread and data collection happens invisibly?

Algorithmic bias - How do we prevent psychological harm when algorithms encode and amplify existing social biases?

Digital addiction - As we better understand the neuroscience behind compulsive technology use, what responsibilities do designers and platforms have?

Privacy and surveillance - What are the psychological impacts of constant observation, data collection, and privacy erosion?

Looking forward, the field faces several exciting developments and challenges:

Integration with neuroscience - Combining brain imaging with digital behavior analysis promises deeper insights into technology's neurological impacts.

Cultural dimensions - Expanding research beyond WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) populations to understand cultural variations in cyber-behavior.

Developmental perspectives - Understanding how digital natives who have never known a world without the internet may develop fundamentally different psychological processes.

Regulatory frameworks - Developing evidence-based policies that protect psychological well-being without stifling innovation.

Conclusion

From text-based chat rooms to immersive virtual worlds, from basic behavioral observations to sophisticated theoretical frameworks, cyberpsychology has evolved dramatically in just three decades. What began as a niche interest has become essential for understanding human behavior in contemporary society, where the average person spends over six hours daily in digital environments.

As AI systems become more sophisticated, virtual environments more immersive, and the boundaries between physical and digital reality increasingly permeable, cyberpsychology stands at a fascinating frontier. The questions it addresses are no longer academic curiosities but urgent matters of public health, social cohesion, and what it means to be human in an age where our minds increasingly exist across both carbon and silicon substrates.

Perhaps the most profound insight from three decades of cyberpsychology research is that technology is neither inherently harmful nor beneficial to human psychology—it amplifies our existing tendencies, creates new possibilities for both connection and alienation, and reshapes our cognitive landscape in ways we're still working to understand. As we navigate this evolving relationship, cyberpsychology will remain an essential guide, helping us maintain our humanity while embracing technology's transformative potential.

The question is no longer how technology is changing us—that much is certain. Rather, we must ask: How do we want to be changed? What aspects of human psychology should we safeguard, and what might we willingly transform as we continue our psychological evolution in partnership with the technologies we create?