Comfortable Surveillance - How Smart Tech Is Rewiring Trust, Privacy, and the Human Psyche

SURVEILLANCE & SOCIETY

Your smart TV knows what you watched last night. So does your fridge. Your voice assistant quietly processes your conversations, and your doorbell camera watches the street while you sleep. In the span of a single generation, we have invited an unprecedented level of surveillance into our most private spaces, trading intimate behavioral data for the convenience of connected living.

This isn't the dystopian surveillance state that George Orwell envisioned—it's far more subtle and infinitely more personal. We willingly purchase these devices, configure them ourselves, and often defend them when questioned. Yet beneath this comfortable arrangement lies a profound psychological transformation that is quietly rewiring how we think about trust, privacy, and human autonomy.

Surveillance capitalism has emerged as the dominant economic model of the digital age, where companies monetize personal data collected from our online and offline activities. This system operates through passive data collection—the continuous gathering of information about our behaviors, preferences, and routines without explicit awareness or consent for each data point collected. The result is behavioral profiling: the creation of detailed psychological and behavioral portraits used to predict and influence our future actions.

The central tension of our time is not whether we are being watched, but how comfortable we have become with being watched—and what this comfort is doing to us.

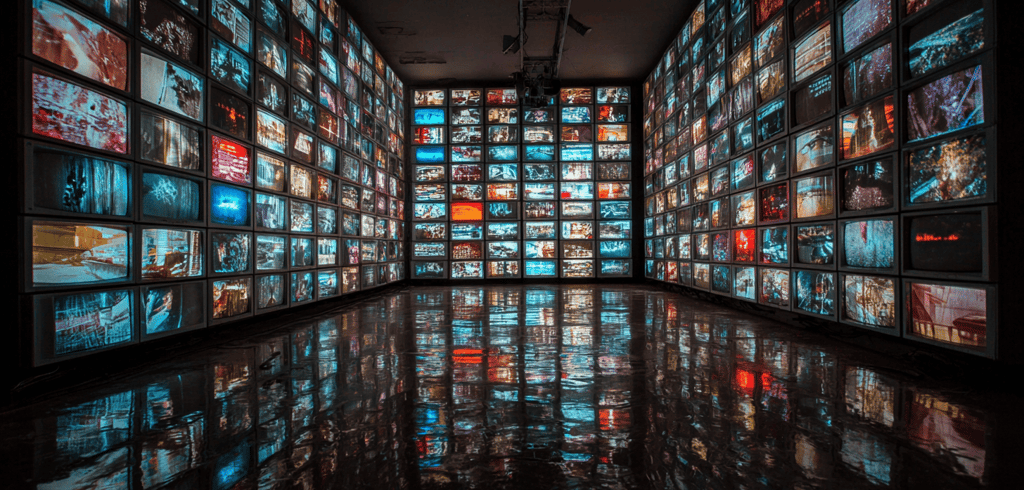

The Digital Mirror - Smart TVs and the Data Economy

Smart televisions have become digital mirrors, reflecting not just entertainment but intimate portraits of who we are. Through Automatic Content Recognition (ACR) technology, these devices function as "Shazam-like technology for audio/video content," continuously monitoring viewing habits for advertising and profiling purposes. They collect information about channels and networks watched, websites visited, programs viewed, and time spent viewing, extending this surveillance to any connected device.

The psychological implications of this behavioral profiling extend far beyond targeted advertising. When Netflix suggests a show that perfectly matches your mood, or when your TV seems to anticipate your viewing preferences with uncanny accuracy, you are experiencing the psychological effects of algorithmic intimacy. These systems know your entertainment patterns better than you consciously know them yourself—they understand your stress-watching habits, your late-night preferences, your weekend binges.

This creates a unique form of psychological feedback loop. The more accurately these systems predict your behavior, the more they shape your future choices. You begin to see yourself through the lens of algorithmic recommendations, potentially narrowing your cultural horizons to what the system believes you will engage with. The psychological concept of the "looking-glass self"—how we develop our identity through how we believe others perceive us—takes on new meaning when the "other" is an algorithm that has analyzed thousands of hours of your private entertainment choices.

Perhaps most concerning is the erosion of informed consent. All major smart TV manufacturers, including Samsung and LG, implement ACR technology, yet most users remain unaware of the depth and breadth of data collection occurring in their living rooms. The complexity of privacy settings and the length of terms of service agreements mean that true informed consent becomes practically impossible. Users click "agree" not because they understand and accept the trade-offs, but because the alternative—a non-functional device—is unacceptable.

Invisible Eyes - Smart Devices and Shifting Human Boundaries

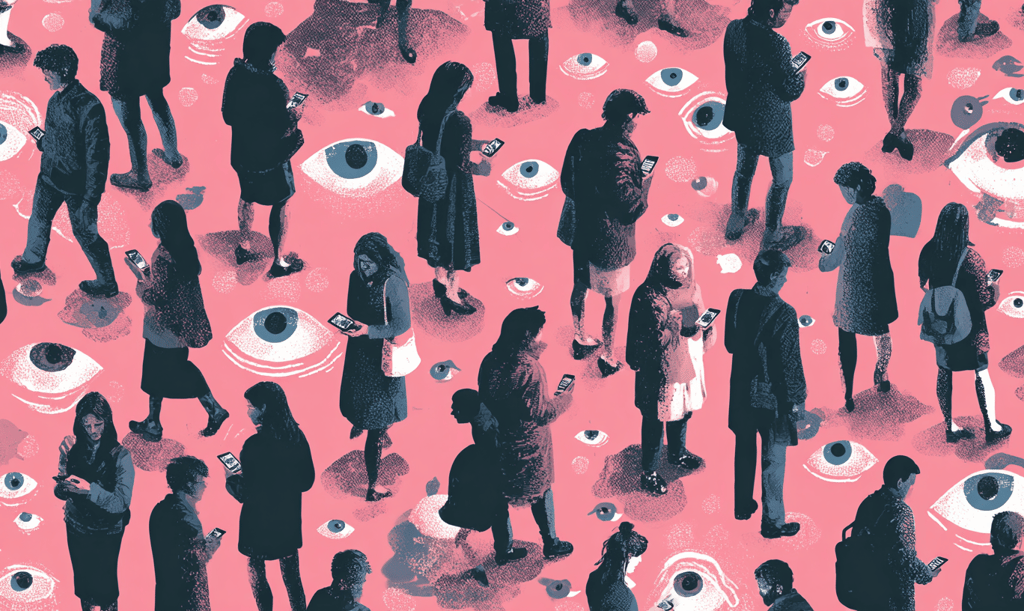

The proliferation of smart home devices has fundamentally altered the psychological geography of private space. Alexa listens in bedrooms, Google Nest cameras watch children play, and smart refrigerators track eating patterns. Even when these devices aren't actively recording, their presence creates what researchers call "ambient surveillance"—the psychological state of existing under potential observation.

This ambient surveillance triggers subtle but significant changes in social behavior. Family conversations become more guarded when a voice assistant is present. Couples modify their arguments, knowing that heated discussions might be captured and processed. Children grow up in homes where their tantrums, laughter, and private moments are potentially monitored by corporate algorithms designed to extract insights about developing consumer preferences.

The psychological impact extends beyond behavioral modification to include the fundamental blurring of public and private space. Traditionally, the home served as a sanctuary from social surveillance—a place where individuals could be their authentic selves without performance or judgment. Smart devices eliminate this psychological boundary, creating what amounts to a 24/7 focus group in your most intimate space.

This shift manifests in various psychological adaptations. Some people develop "device paranoia," regularly unplugging smart devices or covering cameras when engaging in private activities. Others experience "privacy fatigue," eventually giving up on maintaining boundaries they feel powerless to protect. Still others embrace "performative privacy," making a show of turning off devices while secretly feeling surveilled regardless.

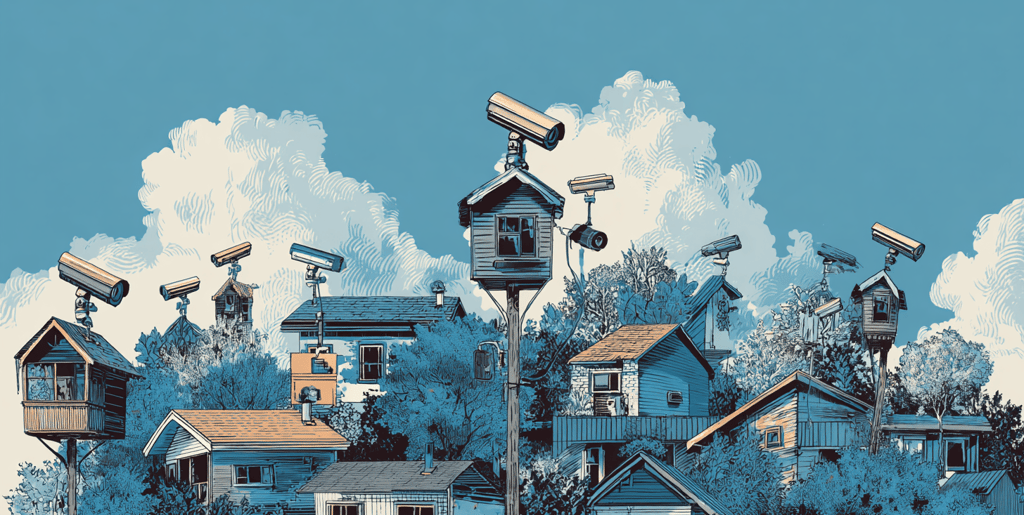

The presence of doorbell cameras and security systems extends this psychological shift to the threshold between private and public space. Neighbors become inadvertent subjects of surveillance, creating new social tensions around consent and observation. The psychology of neighborhood watch—once a community-organized response to security concerns—becomes individualized and corporatized, with each household potentially monitoring others through their smart security systems.

Comfortable Surveillance - Why We Say Yes to Being Watched

The most fascinating aspect of the smart home surveillance ecosystem is not that it exists, but that millions of people actively choose to live within it. Understanding this choice requires examining the complex psychology of trade-offs, cognitive dissonance, and adaptation that characterizes modern digital life.

The fundamental trade-off appears straightforward: convenience versus privacy. Smart devices genuinely make life easier. Voice assistants answer questions instantly, smart thermostats optimize energy usage, and connected appliances can be controlled remotely. These benefits are immediate, tangible, and personally experienced. Privacy costs, by contrast, are abstract, future-oriented, and often invisible. It's psychologically natural to prioritize concrete present benefits over hypothetical future harms.

However, the psychology of these trade-offs is more complex than simple cost-benefit analysis. Cognitive dissonance—the mental discomfort caused by holding contradictory beliefs—plays a crucial role in maintaining comfort with surveillance. Most people simultaneously believe that privacy is important and that their smart devices are listening to everything they say. To resolve this discomfort, they often rationalize the surveillance: "I have nothing to hide," "It's just for advertising," or "The convenience is worth it."

This rationalization process is aided by what psychologists call the "privacy paradox"—the gap between stated privacy concerns and actual privacy behaviors. People express concern about digital surveillance in surveys but continue to use surveilled devices in practice. This paradox isn't evidence of hypocrisy; it's evidence of the psychological difficulty of making privacy-preserving choices in a world where such choices come with significant social and practical costs.

Privacy fatigue represents another crucial psychological adaptation to pervasive surveillance. After years of data breaches, privacy policy updates, and security alerts, many people simply stop engaging with privacy management. The cognitive load of maintaining digital boundaries becomes overwhelming, leading to a form of learned helplessness where people accept surveillance as an inevitable fact of modern life.

This acceptance is reinforced by social proof—the psychological tendency to look to others' behavior when making decisions. When everyone in your social circle has smart devices, when your friends share their data with tech companies, when surveillance becomes normalized through social media and digital services, resistance feels antisocial and futile.

Trust, Control, and the Surveillance Paradox

Living under constant surveillance paradoxically both erodes and creates new forms of trust. The traditional trust relationships that anchor human society—between family members, friends, neighbors, and communities—become complicated when digital intermediaries are always present, listening, and learning.

Institutional trust particularly suffers under surveillance capitalism. Surveillance capitalism involves "the unilateral claiming of private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data," which are then "computed and packaged as prediction products and sold into behavioral futures markets". This process happens without meaningful consent or democratic oversight, creating what researchers describe as a breakdown in the social contract between individuals and the institutions that govern their digital lives.

Yet people continue to trust these systems with their most intimate data. This trust is partly based on illusory control—the psychological tendency to overestimate one's ability to control outcomes. Privacy settings, opt-out options, and data management tools provide a sense of agency over personal information, even when the complexity of data collection makes true control practically impossible. The mere existence of privacy controls, regardless of their effectiveness, creates psychological comfort.

The surveillance paradox emerges from this gap between perceived and actual control. People feel both surveilled and protected, both vulnerable and empowered. Smart home security systems exemplify this paradox: they provide genuine security benefits while simultaneously creating new vulnerabilities and surveillance exposures. The psychological comfort of protection outweighs the abstract concern about corporate surveillance.

Constant background monitoring creates its own psychological effects. Some people report low-level anxiety about their devices, wondering what they're recording or whether they're being judged by algorithmic systems. Others develop superstitious behaviors around their devices, speaking to them politely or avoiding certain topics in their presence. These behaviors suggest that people are psychologically processing these devices as social entities rather than mere tools.

The most profound psychological impact may be the gradual normalization of surveillance as a condition of modern life. When surveillance becomes ambient and constant, the psychological category of "privacy" begins to shift. Privacy becomes not the absence of observation but the management of observation—not being unseen but being seen on your own terms.

Reclaiming Autonomy in a Smart World

The psychological transformation wrought by smart device surveillance is not predetermined or irreversible. Understanding these dynamics creates opportunities for more conscious engagement with surveillance technologies and the development of healthier psychological boundaries in digital environments.

Privacy hygiene represents one approach to maintaining psychological autonomy within surveilled systems. This involves developing regular practices for managing digital boundaries: reviewing privacy settings, understanding data collection practices, and making conscious choices about device usage. Like physical hygiene, privacy hygiene requires ongoing attention and maintenance rather than one-time solutions.

Awareness campaigns and digital literacy education can help people understand the psychological dynamics of surveillance capitalism. When people recognize how their behavior is being shaped by algorithmic systems, they can make more intentional choices about their engagement with these technologies. This doesn't necessarily mean rejecting smart devices entirely, but rather using them more mindfully.

Community norms around surveillance can create social support for privacy-protecting behaviors. When communities develop shared standards for appropriate surveillance and data sharing, individual resistance becomes less psychologically taxing. These norms might include agreements about home security cameras, social media sharing of family activities, or expectations around voice assistant usage in shared spaces.

The development of alternative technologies that prioritize user autonomy over data extraction offers another path forward. Open-source smart home systems, privacy-focused devices, and decentralized alternatives to corporate platforms can provide convenience without surveillance. Supporting these alternatives, even when they require more technical knowledge or come with higher costs, represents a form of technological resistance.

Perhaps most importantly, maintaining psychological autonomy requires ongoing critical reflection about the relationship between convenience and control. The question isn't whether smart devices are inherently good or bad, but whether we are conscious enough about their effects to make choices that align with our values and psychological well-being.

The smart home revolution has irrevocably changed the psychological landscape of private life. The challenge now is not to reverse this change but to navigate it with greater awareness, intentionality, and respect for human psychological needs. The devices that promise to make our lives easier should not make our inner lives more complicated, more surveilled, or less autonomous.

The question that remains is deeply personal: Is convenience worth the cost of always being watched—and how would you know if the price is too high? The answer requires not just intellectual analysis but ongoing psychological self-assessment. In a world of smart devices, the smartest thing we can do is remain conscious of how they are changing us.

What smart devices do you use daily—and how do they make you feel about your privacy? Let's talk about it in the comments.